Postcard Stories From Paris – Week One

While I’m in Paris, I’ve been writing a Postcard Story every day based on the art I’ve been able to see. It’s been a great excuse to get out and visit some of the city’s amazing museums. Here’s my first week of tiny art stories.

1st January 2020

Paris, France

Maureen Robinson

Late-ish for a Kandinsky, Deux Points Verts -or Two Green Points, to give this painting its cumbersome, English dues- is composed of overlapping coloured strips. To the left of the canvas the tones are bolder: black and green, with a mustard red dollop like leakage from a cheap hamburger or the ghost of hedonism past. If this is youth, the mid-section’s beauty and formed from custardy pastel blocks. It is possible with light, or gently squinting, to romance the outline of four soft hearts and, to the right, where the fourth heart’s dripping, the whimsical notion of a kite. If this is beauty, then loss must follow, for Kandinsky was fading by this point. The final third is marked by the absence of colour: white, more white and beige, a pink, so pale it’s barely breathing, and gray, which is colour’s poor shadowy twin. A black snakes corrugates though these last dull panels, its splayed jaws stretching beyond the pink to nip the canvas edge. And what of the afore-mentioned points? Where does Kandinsky situate them? Look to the section where the colours are kindest. Look to the space above those sweet hearts. Note two green dots, like a drunken colon, where temptation first sinks its poisoned fangs in.

2nd January 2020

Paris, France

Ciler Ilhan

It is cold in Paris and recently raining. From the fifth floor of the Centre Pompidou the skyline looks to be sepia-tinted, like a snapshot taken in Victorian time. The Tower’s part ghosted by the clouds. The Seine’s a mere smudge on the camera lens. Meanwhile, back at the Pompidou, the west terrace is running slick with puddles. Damn the tourists and their Iphones. It’s maintenance only outside today. Which doesn’t stop the tourists hovering round all four sides of the terrace, pressing their phones against the glass; to Hell with flashback and window flare. In the courtyard, glassed like the exhibits they actually are, Henri Laurens’ enormous nudes squirm and contort their thick bronzed limbs. Arms wrapped like bandages round their torsos, knees drawn primly to their shins, they are sculptures first and statues second. Making it impossible to read their dead pan faces, their lips reduced to blockish lines, foreheads like cliffs, eyes like stuck on pistachio shells. Body language can only say so much when you’re cast in metal and stuck both-footed to a plinth. Perhaps the nudes are mortified by all this staring. Perhaps they’re trying to cover their shame. Or maybe, they’re just like the rest of us; doing whatever they can to stay warm.

3rd January 2020

Paris, France

Marta Dzido

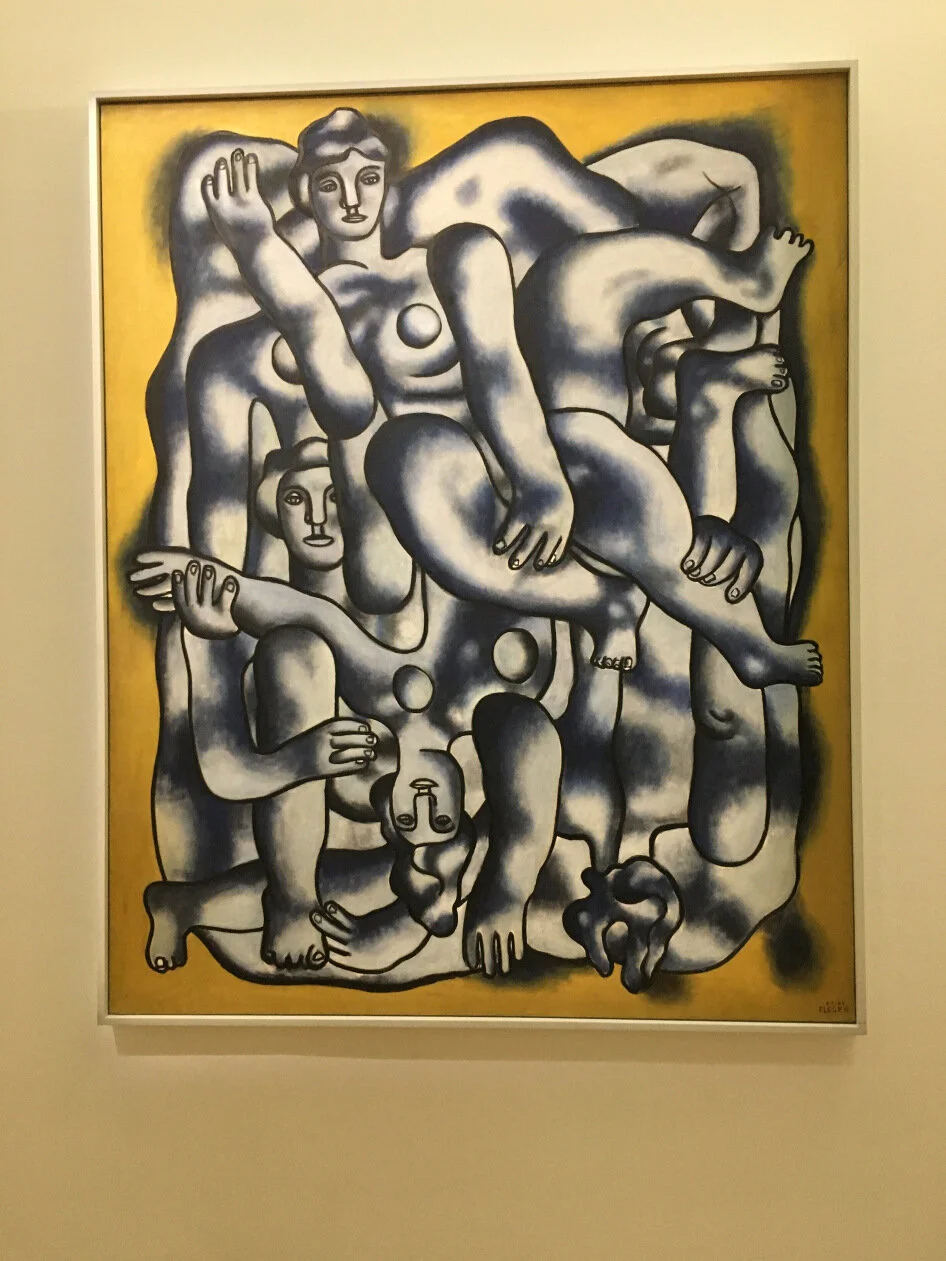

I’ve stood for ages in front of Fernand Leger’s “Acrobates en Gris,” carefully counting. Three nude women in various shade of photocopier gray are tangled together against a mustard backdrop, their limbs creating the semblance of a rectangle. And while it seems like there are too many shoulders for the three stony faces glaring back at me, sure it’s almost impossible in an orgy set-up, to tell a shoulder from a knee or any other folded joint. It’s the hands that are really bothering me. I’ve counted clockwise round the frame at least a dozen times or more. The museum’s attendants beginning to hover suspiciously. It’s like untangling skeins of wool or tracing your way out of a children’s maze. Here’s a hand, and here’s a second, and there are six more. That makes eight. Which is two too many for a beast that’s only got three faces and a correctly apportioned half dozen feet. The extra hands aren’t the worst of it. Leger paints breasts like small, French boules, balanced awkwardly upon the chest, and les trois acrobates I’m currently scrutinizing appear to be juggling just four such rounds between the three of them. Now, I’m frozen in front of the painting, wondering which I’d rather- extra hands or missing breasts?

4th January 2020

Paris, France

Micheal McCann

This afternoon I’m drinking coffee in a café in Montparnasse. I’m thinking about the French-Hungarian sculptor, photographer and writer Brassai who moved to this neighbourhood in 1924 and taught himself how to speak and write French by meticulously reading Proust. Which led, no doubt, to verbosity and an inability to be concise. Note, if you will, the writer, Henry Millar’s bold claim in 1976 that Brassai’s biography of his life was padded, full of factual errors and false impressions not based on fact. Had he not been dead already this nod to Brassai’s many faults, might have been a passing comfort to Ambrose Vollard, the French art dealer whose likeness Brassai sculpted posthumously, sometime around 1950. In this piece, which is now mounted on a wooden stand and displayed within a small, glass case, the poor chap looks like a baked potato who’s gone twelve rounds with a bigger spud.

5th January 2020

Paris, France

Liz Nugent

Henri Matisse- Le violiniste a la fenetre. (Spring 1918)

The violinist is at the window. The violinist is a man. The violinist has his back to me. The violinist is possibly shoeless or wearing socks the colour of skin. The violinist is standing upon a terracotta floor. The violinist may or may not be suffering from cold feet. The violinist is looking through the window, past a balcony and a hedge. The sky beyond is fire red. The violinist thinks the sky is burning. The violinist doesn’t really care so long as it does not stop him playing. The violinist plays violin music. Though I’ve no way of knowing which piece or tune, it is inferred in the way the violinist is gazing upwards, whilst holding his arm at a jaunty angle, that this is not a melancholy air. The violinist is probably thinking, “I am glad that I’m not a pianist for it would not be possible to stand in this window, playing music on a piano, watching the sunset gently burn.”

6th January 2020

Paris, France

Amina Jama

Guiseppe Penone – Respirare Lombra. (1999-2000)

A room constructed of chicken wire and half a million dry bay leaves should not make you want to weep. It’s not the smell of your mother’s spice rack, or your grandmother’s larders, or a forest towards the end of summer, though each of these is a sentiment. Nor is it the sound, which is silence padded, so you hear for the first time in several months, your own voice simmering inside your head and perhaps admit -for there’s only leaves listening- that it is reluctant and a little sad. Neither is it the thought of Australian forests, flaming on the other side of the world, though this thought, if allowed to settle, is enough to make the whole gallery weep. No, it’s something to do with the rhythm; the sound of your own lungs losing air. And if the artist happens to claim, that men and trees breathe to a different rhythm, you’d have to agree he’s on to something. You can feel it here, in this parchment room; the distance looming between created things.

7th January 2020

Paris, France

Anja Ivic

If my French is to be trusted, then Maya Dunietz’s 2016 installation, Thicket is constructed from eleven thousand five hundred sets of white plastic headphones, woven together in a back lit cloud. The lump of it wilting delicately from the ceiling resembles a dollop of unbaked meringue or some drunken notion of a chandelier. The floor’s a frenzy of tangled shadows -branched, broken, criss-crossed, spliced- like the shattered windscreen of a car. The room seems cold, though it is isn’t. There’s an assumption here of frost. And the sound is similarly icy. It zips. It buzzes. It occasionally trings. It pursues me round the gallery like an insect trapped inside the ear. All this to say, it should be dreadful. It should be feedback and tinnitus and that static hum when the TV runs out. It should feel like an itch inside the brain. Worse still, it should speak of every lead I’ve ever tangled, ever necklace, thread and cord; the actual cheap, white, plastic headphones currently lying at the bottom of my bag, hopelessly knotted around my house keys and a biro I nicked from a German hotel. But it doesn’t. It isn’t. It’s somehow holy; this space saturated with cheap white noise. It goes against the laws of logic. Ugly on ugly on ugly on ugly eventually equates to sublime.